Effective Well Control Strategies for Tight Gas Reservoir Drilling

Tight gas reservoirs are one of the biggest frontiers in energy production today. These enormous resources are locked into rock formations of very low permeability, and their extraction is quite a technically challenging task. For drilling engineers and well site leaders, this complexity means primarily one thing: well control. Most conventional methods fail in meeting the peculiar pressure profiles and geological parameters exhibited by tight gas. This paper covers the nature of these reservoirs and provides a holistic framework of strategies, technologies, and training methodologies that have become imperative for conducting safe and efficient drilling operations.

What are the Tight Gas Reservoir Characteristics?

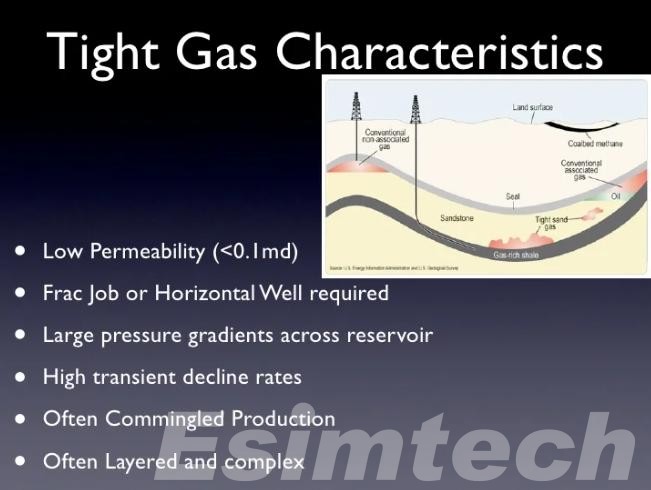

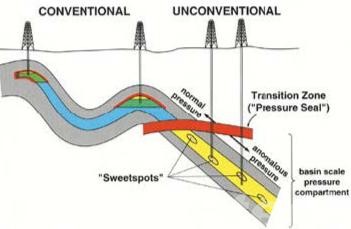

The first thing to learn about well control in tight gas drilling is the basic foe: the rock itself. Tight gas reservoirs are not characterized by the absence of gas; rather, they are characterized by the extreme difficulty of liberating it. Essentially, they are geologic prisons that host huge volumes of natural gas within a rock matrix of incredibly low permeability.

The core of the challenge is in the impermeability of the rock. In measurements of microdarcies, the permeability of these formations is many orders of magnitude lower than those of conventional sandstone reservoirs. Imagine the difference between drawing water through a sponge versus through solid marble. This means that the gas cannot flow freely to the wellbore without artificial intervention; hence, advanced techniques such as horizontal drilling and massive hydraulic fracturing become not only beneficial but also necessary.

From a drilling and pressure management point of view, this geology forms a critical condition named the narrow drilling margin or "narrow mud window." This is the dangerously thin pressure envelope between:

- Pore Pressure: The minimum bottomhole pressure required to suppress formation fluids and prevent a dangerous influx (a "kick").

- Fracture Gradient: The pressure that the wellbore wall can resist before it fractures; when that happens, lost circulation occurs, and drilling fluid invades the formation.

In conventional reservoirs, this window is wide, affording a comfortable operating range. In tight gas formations, it's notoriously constricted. As a result, drilling engineers must maintain a continuous high-wire act, precisely balancing the mud weight so as to stay within this narrow band. This incessant balancing act-teetering between causing a kick on one side and inducing lost returns on the other-is the defining characteristic shaping every aspect of effective well control strategies for tight gas reservoirs. It is the fundamental problem that all subsequent technologies and procedures are designed to solve.

Common Well Control Challenges in Tight Gas Drilling

But the defining characteristic of tight gas-the narrow drilling window-makes drilling difficult and, more importantly, it creates a unique set of well control dilemmas where conventional responses can make a bad situation worse quickly. The following are the most common and dangerous threats to safe operations:

1. Delayed Influx Detection

A kick in a conventional reservoir announces its presence by relatively obvious surface indications. In a tight gas reservoir, the very low permeability serves as a choke, allowing the gas to seep into the wellbore at an agonizingly slow rate. This "silent kick" means that by the time a rig crew notices an appreciable pit gain or flow anomaly, a significant and dangerously swellable quantity of gas might have already invaded the well. This critical time loss for the detection of the kick drastically reduces the window of opportunity for a controlled response and transforms an easily controllable influx into a fully-fledged well emergency.

2. Simultaneous Kick and Lost Circulation

This is the ultimate "damned if you do, damned if you don't" scenario. The wellbore often traverses multiple pressure regimes. While controlling a kick from a high-pressure lower zone by increasing the mud weight, you can easily exceed the fracture gradient of a shallower, weaker zone. This results in lost circulation, where drilling fluid is lost to the formation. The loss of fluid drops the hydrostatic pressure in the annulus, which can, in turn, induce a further influx from the high-pressure zone. This creates a vicious and self-perpetuating cycle that renders standard, sequential well control procedures ineffective and demands highly specialized adaptive well control procedures.

3. When the Cure Harms

One of the primary rules in well control for conventional wells is to shut the well in when a kick is detected. In a tight gas well with a narrow window, this could prove disastrous. The rapid pressure increase due to closure of the BOPs can easily exceed the fracture gradient at the casing shoe and split the rock. The result could be an underground blowout where fluids would escape vertically into other formations rather than being safely contained and circulated out at the surface. In fact, this very risk dictates a revision in the shut-in considerations.

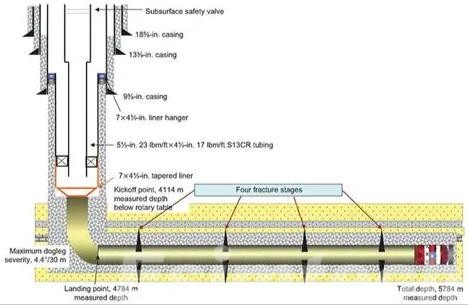

4. HP/HT and Wellbore Geometry

These challenges are frequently accentuated by HP/HT conditions, which are common in deep tight gas plays; high temperatures can degrade properties of drilling mud, while high pressures require more precise pressure management. Likewise, complex geometries of the wellbore, like very long horizontal sections, produce additional friction and pressure losses that make it even more difficult to keep the entire open hole section within the narrow pressure window.

Essentially, tight gas drilling is a set of interrelated problems. A single issue, like a slow influx, can rapidly cascade into a complex well control event, testing the limits of both technology and human expertise.

Proactive & Preventive Well Control Strategies

Waiting for a problem to arise is not an option in the high-stakes environment of tight gas drilling. A reactive stance almost guarantees a complex well control incident that will be costly. Safety and efficiency are thus founded on a paradigm of proactive engineering and preventive design: an integration of multiple layers of defense into the well plan long in advance of running the first piece of drill pipe.

1. Fundamental Protection

Sound Well Architecture and Casing Design The first and most important line of defense is the structural blueprint of the well. A good well design is a strategic pressure-management system. The primary tactic involves the careful placement of casing strings and liners in order to compartmentalize the wellbore. Each casing string is set to isolate a particular narrow-margin section, thereby "resetting" the pressure window for the succeeding drilling phase. This approach ensures that the formation strength at the casing shoe is always adequate to resist the pressures encountered during deeper drilling.

2. The Predictive Edge

Advanced Pore Pressure and Fracture Gradient (PPFG) Modeling

You cannot manage what you cannot measure, and you cannot prepare for what you cannot predict. Use of generic models is a recipe for disaster in tight gas. Success is dependent upon development of a high-fidelity, well-specific PPFG model. This is done by synthesizing all available data:

- Seismic attributes and velocity analysis for regional pore pressure trends.

- Detailed offset well analysis including mud weight histories, gas shows, and leak-off test results.

- Real-time LWD logging, like resistivity and sonic logs, serve as direct indicators of the formation pressure while drilling.

The continuously calibrated model provides the "roadmap" of expected pressures, enabling the engineer to foresee narrow windows and plan mud weights and casing points with precision, thus turning uncertainty into a managed risk.

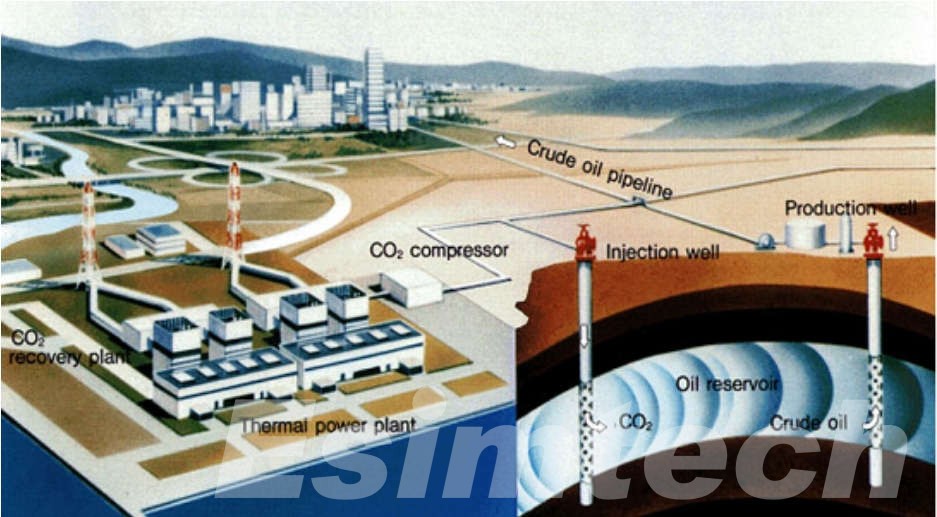

3. The Dynamic Barrier: Engineered Drilling Fluids and ECD Management

The drilling fluid is the dynamic, circulating barrier against formation pressures. In tight gas drilling, it must be treated as a precision-engineered tool rather than just a cuttings-removal medium. The emphasis is on designing a fluid system that possesses optimum rheological properties to minimize ECD, or the increase in bottomhole pressure resulting from fluid friction during circulation. This ECD spike can be dramatically reduced with the use of specialized lubricants, low-gel-strength muds, and synthetic-based fluids. The goal is to create a fluid that exerts enough static pressure to hold the formation but does not see a dramatic pressure increase when circulated, keeping the entire pressure profile safely within the narrow drilling window.

By integrating robust architecture, predictive modeling, and a precision-engineered fluid system, the well is transformed from a vulnerable hole in the ground into a controlled and monitored pressure vessel. This multi-layered, proactive approach forms the bedrock of effective well control in tight gas drilling-designed not to react to crises but to prevent them from ever occurring.

Advanced Drilling & Well Control Technologies

Conventional equipment and methods often reach their operational limits when drilling through the challenging pressure environment of tight gas reservoirs. To be successful in these conditions, technologies that provide enhanced precision, control, and real-time insight are required. The following advanced systems have become indispensable for managing the narrow margin between pore and fracture pressure.

1. Managed Pressure Drilling: Precision Pressure Control

Managed Pressure Drilling is not an accessory, but a change of paradigm: it changes well control from an after-the-fact emergency procedure to a proactive, on-going process. The heart of MPD is a closed circulating loop, closed at the surface with a Rotating Control Device (RCD), which allows for the application of accurate annular backpressure via a separate choke manifold.

The strategic value of MPD in tight gas is multifaceted:

- Active window management is maintained by manipulating surface backpressure to fine tune the bottomhole pressure, enabling it to stay within the narrow drilling margin, therefore "walking the line" between influx and loss.

- Improved Early Kick Detection: The closed system, combined with a Coriolis flow meter at the returns line, offers unparalleled sensitivity. It can detect minute discrepancies between flow-in and flow-out volumes—often as little as a few gallons—providing the crew with critical extra minutes to respond to an influx before it becomes significant.

Reduced NPT: MPD significantly reduces the non-productive time associated with well control events and mud loss remediation by minimizing fluid losses and mitigating pressure spikes.

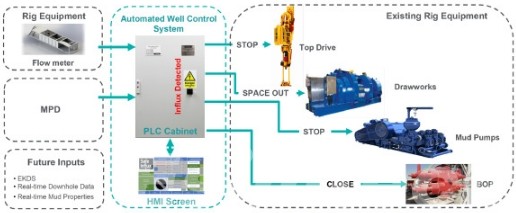

2. Advanced Early Kick & Loss Detection Systems

While MPD provides a control mechanism, advanced monitoring systems are its sensory organs. These systems utilize high-frequency data and sophisticated algorithms to see what the human eye cannot.

- Coriolis Flow Meters: These provide highly accurate, real-time measurements of both the flow rate and density of the fluid returning from the well. A subtle increase in return flow or a decrease in density is one of the earliest indicators of gas influx.

- Automated Pit Monitoring: Modern systems track total active volume continuously with extreme precision, without the guesswork and lag time of manual pit checks.

- Real-Time Pressure Monitoring: Pressure-While-Drilling tools continuously send downhole pressure data. This allows the engineers to visualize the actual pressure environment at the bit and compare it directly to the predicted PPFG model.

These systems, integrated on one dashboard, are able to deliver a robust early kick detection capability that transforms subtle anomalies into clear, actionable alarms.

2. The Integrated Data Platform: From Information to Insight

It is only when all these technologies come together within an operating platform that their true power can be realized. Such a platform integrates real-time data from the MPD system, EKD sensors, downhole tools, and surface drilling parameters. Advanced software algorithms analyze this stream of data to:

- Provide Predictive Alerts: Model the hydraulic response of the well to predict issues before they actually happen.

- Visualize the Pressure Window: Providing engineers with a clear, real-time picture of where the current pressure profile sits relative to the pore and fracture pressures.

- Enable informed decision-making by providing the quantitative foundation necessary for conducting complicated adaptive well control procedures with confidence.

In summary, these advanced technologies create a synergistic shield. The monitoring systems provide the early warning, the MPD system delivers the precise control, and the integrated platform offers the situational awareness to bind it all together. This technological triad is that which makes safe and efficient drilling in complex tight gas reservoirs not just possible, but predictable.

Adaptive Well Control Procedures

In the tight gas drilling environment, conventional well control practices may inadvertently turn an incident that is otherwise controllable into a major problem. The narrow margin between pore and fracture pressure requires abandoning inflexible, cookbook well control practices for well control procedures in fluid adaptation. These customized approaches will involve managing the downhole pressures with sophistication, using precisely the correct response, given both the ever-changing situation and the technologies at hand.

Key adaptive procedures include:

- Modified Shut-In Protocols: With the modified shut-in protocols, instead of an immediate hard shut-in that may create damaging pressure surges, a controlled "soft shut-in" is often implemented. The idea is to very carefully close the BOP in a particular sequence so that the risk of inducing fractures at the casing shoe may be minimized.

- MPD Driller's Method: The response to an influx for wells equipped with a Managed Pressure Drilling system is fundamentally different. The well can often be controlled without a conventional shut-in. Utilizing the MPD choke manifold, drillers can apply precise surface backpressure so as to circulate the kick out, all the time maintaining a constant safe bottomhole pressure throughout the operation.

- Bullheading and Loss Control Mitigation: This is a critical well intervention operation in cases of a severe kick-loss scenario where it is not feasible to circulate the influx. That is, drilling fluid is pumped down the wellbore with a pressure that is high enough to bullhead the influx back into the formation and re-establish well control, even if some temporary fluid loss occurs.

Ultimately, the success of these adaptive procedures depends upon pre-well planning and crew proficiency. Decision trees on when to apply a soft shut-in, start dynamic MPD control, or approve a bullheading operation must be created and simulated long before drilling reaches the target zone. This proactive engineering makes certain that when presented with a well control event of high complexity, the team's response is not one of improvisation but of implementing a pre-approved, well-rehearsed plan tailored to the unique challenges of tight gas reservoir drilling.

Training and Competency: How Simulation Work?

Basically, tight gas drilling has no room for error, and therefore, theoretical knowledge is not enough. High-fidelity well control simulation training bridges the gap between what is learnt in the classroom and what is executed in the field. Modern drilling simulators are sophisticated platforms that replicate the rig floor and downhole physics with remarkable accuracy, creating a dynamic and risk-free environment for mastering complex scenarios.

These simulators work by taking in real-world inputs and running them through sophisticated hydraulic and thermodynamic models in real time. When a trainee takes an action-say, moving a choke or shutting in a well-the simulator calculates the effect on downhole pressures, gas migration, and fluid flow on the fly, displaying the results on realistically modeled control panels. This technology enables focused training on tight gas drilling challenges, including:

- Recognizing and responding to subtle "slow kick" indications.

- Carrying out the MPD Driller's Method for controlled influx circulation.

- Managing the extreme complexity of simultaneous kick-loss scenarios.

Eventually, simulation turns theoretical knowledge into instinctive competence. Through repetitive practice in simulated high-consequence emergencies in a safe environment, drilling crews develop the muscle memory, decision-making speed, and team coordination necessary to maintain well control in the extreme pressures of real operations.